6. Dictionaries¶

A dictionary, or dict, is like a list, but more general. In a list, the indices have to be integers; in a dictionary they can be (almost) any type.

You can think of a dictionary as a mapping between a set of indices (which are called keys) and a set of values. Each key maps to a value. The association of a key and a value is called a key-value pair or sometimes an item.

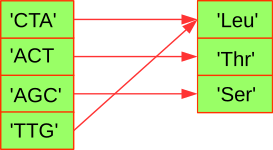

As an example, we’ll build a dictionary that maps from codons to amino acids, so the keys and the values are all strings.

The function dict() creates a new dictionary with no items. Because dict is the name of a built-in function, you should avoid using it as a variable name.

cod2aa = dict()

print(cod2aa)

print(type(cod2aa))

{}

<class 'dict'>

The curly-brackets, {}, represent an empty dictionary.

You can also create an empty dictionary with the curly brackets ({}), just like you can create an empty list with square brackets ([]).

cod2aa = {}

print(cod2aa)

{}

To add items to the dictionary one at a time, you use square brackets:

cod2aa['CTA'] = 'Leu'

This line creates an item that maps from the key 'CTA' to the value 'Leu'. If we print the dictionary again, we see a key-value pair with a colon between the key and value:

print(cod2aa)

{'CTA': 'Leu'}

This output format is also an input format. For example, you can create a new dictionary with 3 items:

cod2aa = {'CTA': 'Leu', 'AGC': 'Ser', 'ACT': 'Thr'}

If you print cod2aa, you will see that the order of the items in the dictionary is the same. The order of items in the dictionary is identical to the order of insertion.

print(cod2aa)

{'CTA': 'Leu', 'AGC': 'Ser', 'ACT': 'Thr'}

Warning

The dictionary order became available in Python 3.6 and is guaranteed from Python 3.7 onwards. If you ever use an older Python version, be aware that this order is not guaranteed and practically unpredictable. In this case you have to assume that a dictionary is unordered!

You can retrieve an item from a dictionary by using the [] square brackets. This is similar as to how you access elements from a list.

print(cod2aa['ACT'])

Thr

The key 'ACT' always maps to the value 'Thr' so the order of the items doesn’t matter.

If the key isn’t in the dictionary, you get a KeyError exception:

print(cod2aa['GGT'])

---------------------------------------------------------------------------

KeyError Traceback (most recent call last)

/tmp/ipykernel_1795/4188483742.py in <module>

----> 1 print(cod2aa['GGT'])

KeyError: 'GGT'

Note

Dictionaries are very similar to lists. The one major difference is that values in a list are always accessed by an integer and that values in a dict can be accessed by a variety of key types.

Because you use keys to look up values, you can understand that keys must always be unique. On the other hand, values do not need to be unique and can be anything, including a list or a dict.

Let us add another codon (key) that maps to an already existing amino acid (value):

cod2aa['TTG'] = 'Leu'

print(cod2aa)

{'CTA': 'Leu', 'AGC': 'Ser', 'ACT': 'Thr', 'TTG': 'Leu'}

The len() function works on dictionaries; it returns the number of key-value pairs:

len(cod2aa)

4

The in operator works on dictionaries; it tells you whether something appears as a key in the dictionary (appearing as a value is not good enough).

'CTA' in cod2aa

True

'Leu' in cod2aa

False

6.1. Dictionary Methods¶

Python provides methods that operate on dictionaries. For example, keys() gives you all the keys of a dictionary, values() gives you all the values, and items() gives you all key:value pairs.

cod2aa = {'TTG': 'Leu', 'CTA': 'Leu', 'ACT': 'Thr', 'AGC': 'Ser'}

codons = cod2aa.keys()

print(codons)

dict_keys(['TTG', 'CTA', 'ACT', 'AGC'])

You see all the values of the keys in cod2aa, which are the different codons. However, you’ll also note an unfamiliar dict_keys() object. If you want to loop over all the keys, this doesn’t matter:

for codon in codons:

print(codon)

TTG

CTA

ACT

AGC

However, if you want to use this object as a list you have to explicitly convert it to list using the list() function.

codons = list(codons)

print(codons)

['TTG', 'CTA', 'ACT', 'AGC']

The values() and items() methods are very similar to keys().

amino_acids = cod2aa.values()

print(amino_acids)

dict_values(['Leu', 'Leu', 'Thr', 'Ser'])

i = cod2aa.items()

print(i)

dict_items([('TTG', 'Leu'), ('CTA', 'Leu'), ('ACT', 'Thr'), ('AGC', 'Ser')])

for codon, aa in cod2aa.items():

print(f"{codon} encodes for {aa}")

TTG encodes for Leu

CTA encodes for Leu

ACT encodes for Thr

AGC encodes for Ser

As with lists, you can use pop() to obtain and delete one key:value pair.

print("before pop:", cod2aa)

p = cod2aa.pop('ACT')

print(p)

print("after pop:", cod2aa)

before pop: {'TTG': 'Leu', 'CTA': 'Leu', 'ACT': 'Thr', 'AGC': 'Ser'}

Thr

after pop: {'TTG': 'Leu', 'CTA': 'Leu', 'AGC': 'Ser'}

6.2. Glossary of useful dictionary terms¶

dict()len()invalues()keys()items()pop()

6.3. Exercises: dictionaries¶

Exercise 6.1

Study the following code:

my_dictionary = {} # initialize empty dictionary. NOTE the curly brackets (as opposed to SQUARE brackets to initialize an empty list)

my_dictionary['green'] = 'color' # key = 'green', value = 'color'

my_dictionary['volvo'] = 'car' # key = 'volvo', value = 'car'

my_dictionary['number_of_fingers'] = 10 # key = 'number_of_fingers', value = 10. Note, value is a number (not a string, so no quotes '')!

print("dictionary:", my_dictionary)

print("value associated with key 'volvo':", my_dictionary['volvo'])

Modify this code such that the dictionary also contains the key/value pair (‘opel’, ‘car’).

Modify this code to add a key/value pair to the dictionary where

10is the key and'number_of_fingers'is the value (so the reverse of key/value pair that is already in the dictionary.

Verify your code by running it and checking the output.

Exercise 6.2

You can also initialize a dictionary as follows:

my_dictionary = {'A':1, 'B':2, 'C':3}

print("dictionary:", my_dictionary)

print("value associated with key 'A':", my_dictionary['A'])

Use this syntax to create the dictionary from the previous exercise.

Exercise 6.3

I want the following code to print the value associated with the key ‘B’. However, the code contains an error.

my_dictionary = {'A':1, 'B':2, 'C':3}

print("value associated with key 'B':", my_dictionary[B])

Run the code and see if you can find where the error is and correct it so that it does print the value associated with key ‘B’.

Exercise 6.4

Study and run the following code:

my_dictionary = {'A':1, 'B':2, 'C':3}

my_dictionary['A'] = 5

print("value associated with key 'A':", my_dictionary['A'])

Question: why is the value associated with the key ‘A’ the number 5 and not the number 1?

Exercise 6.5

Study and run the following code:

my_dictionary = {'A':1, 'B':2, 'C':3}

for variable_1 in my_dictionary:

variable_2 = my_dictionary[variable_1]

print('variable_1:', variable_1, 'variable_2', variable_2)

Question: does the variable named variable_1 contain keys or values from the dictionary?

Question: does the variable named variable_2 contain keys or values from the dictionary?

Question: what would be a more appropriate (more insightful) name for the variable variable_1?

Question: what would be a more appropriate (more insightful) name for the variable variable_2?

Exercise 6.6

Now adapt the code from exercise 6.5 so that it adds 4 to each value retrieved from the dictionary and prints this to the screen, together with the key.

Use the more appropriate variable names instead of variable_1 and variable_2.

NOTE You are not allowed to change the dictionary itself in the process.

So the dictionary will stay like this:

my_dictionary = {'A':1, 'B':2, 'C':3}

But your code should print:

A 5

B 6

C 7

Exercise 6.7

The dictionary esrrb contains the number of Esrrb peaks per chromosome from an Esrrb ChIP-seq experiment (Chen et al. 2008, 13;133(6):1106-17, PMID 18555785).

The dictionary chrsizes contains the length (bp) of each chromosome in the mouse genome (mm9).

esrrb = {

'chr1': 1160,

'chr10': 1171,

'chr11': 1887,

'chr12': 799,

'chr13': 844,

'chr14': 535,

'chr15': 946,

'chr16': 708,

'chr17': 1098,

'chr18': 638,

'chr19': 660,

'chr2': 1771,

'chr3': 838,

'chr4': 1800,

'chr5': 1630,

'chr6': 1088,

'chr7': 1434,

'chr8': 1183,

'chr9': 1286

}

chrsizes = {

"chr1": 197195432,

"chr2": 181748087,

"chrX": 166650296,

"chr3": 159599783,

"chr4": 155630120,

"chr5": 152537259,

"chr7": 152524553,

"chr6": 149517037,

"chr8": 131738871,

"chr10": 129993255,

"chr14": 125194864,

"chr9": 124076172,

"chr11": 121843856,

"chr12": 121257530,

"chr13": 120284312,

"chr15": 103494974,

"chr16": 98319150,

"chr17": 95272651,

"chr18": 90772031,

"chr19": 61342430,

"chrY": 15902555

}

What is the Python command to obtain the number of peaks on chr6?

The number of peaks for chr11 contains a typo. This should be 1878. Correct this in the dictionary

Write a statement that answers the question whether chrX is present in

esrrb.Expand the code of 3 so that the correct key-value pair is inserted in

esrrbin case chrX is missing (chrX has 180 peaks)Get the number of peaks for chrY. What’s going on here?

Using the two dictionaries above, calculate the peak density (number of peaks per bp) for chr15. Do not manually type the numeric data

Write a loop that will print the peak density for each chromosome.

Exercise 6.8

Here is a dictionary, cod2aa, that maps codons to amino acids:

cod2aa = {'TTG': 'Leu', 'AGC': 'Ser', 'CTA': 'Leu', 'ACT': 'Thr'}

Write the definition of a new dictionary,

aa2cod, that maps amino acids to codons. In other words, this dictionary is the reverse ofcod2aa. You can write this by hand, do not yet use Python to create this dictionary.aa2cod = { ...fill in here... }

Which problem did you encounter? Think of a solution for this problem and write the updated dictionary definition.

Now you know what the new dictionary

aa2codshould look like, create the new dictionary using Python. Your code should takecod2aaas input and create theaa2coddictionary for you.

Exercise 6.9

For these excercises you will use a dictionary with codons as keys as amino acids as values. Create this by running this command (using copy-paste):

codons = {

'aaa': 'K', 'aac': 'N', 'aag': 'K', 'aat': 'N', 'aca': 'T', 'acc': 'T', 'acg': 'T',

'act': 'T', 'aga': 'R', 'agc': 'S', 'agg': 'R', 'agt': 'S', 'ata': 'I', 'atc': 'I',

'atg': 'M', 'att': 'I', 'caa': 'Q', 'cac': 'H', 'cag': 'Q', 'cat': 'H', 'cca': 'P',

'ccc': 'P', 'ccg': 'P', 'cct': 'P', 'cga': 'R', 'cgc': 'R', 'cgg': 'R', 'cgt': 'R',

'cta': 'L', 'ctc': 'L', 'ctg': 'L', 'ctt': 'L', 'gaa': 'E', 'gac': 'D', 'gag': 'E',

'gat': 'D', 'gca': 'A', 'gcc': 'A', 'gcg': 'A', 'gct': 'A', 'gga': 'G', 'ggc': 'G',

'ggg': 'G', 'ggt': 'G', 'gta': 'V', 'gtc': 'V', 'gtg': 'V', 'gtt': 'V', 'taa': '*',

'tac': 'Y', 'tag': '*', 'tat': 'Y', 'tca': 'S', 'tcc': 'S', 'tcg': 'S', 'tct': 'S',

'tga': '*', 'tgc': 'C', 'tgg': 'W', 'tgt': 'C', 'tta': 'L', 'ttc': 'F', 'ttg': 'L',

'ttt': 'F'

}

Provide the Python code that uses a loop to print for each codon its sequence and the amino acid it encodes (e.g. “aaa encodes K”).

Extend this code so that that it only prints the codon sequence if it encodes a stop codon.

Create an empty list named

leuusing[]. Loop through thecodondictionary and add all codons for ‘L’ (leucine) to the listleu. After running your code,leushould contain 6 codons.

Exercise 6.10

In this exercise you will compare the behaviour of lists and dictionaries with respect to indexing.

Study and run the following example:

my_list = ['A','B','C'] # initialize the list

my_dictionary = { 0 : 'A', # init the dictionary

1 : 'B',

2 : 'C' }

print("0:", my_list[0], my_dictionary[0])

print("1:", my_list[1], my_dictionary[1])

print("2:", my_list[2], my_dictionary[2])

You should see that for any given index (0, 1 and 2), my_list and my_dictionary return the same value.

Now run the following example:

my_list = ['A','B','C'] # initialize the list

my_dictionary = { 0 : 'A', # init the dictionary

1 : 'B',

2 : 'C',

5 : 'F' }

print("0:",my_list[0], my_dictionary[0])

print("1:",my_list[1], my_dictionary[1])

print("2:",my_list[2], my_dictionary[2])

print("my_dictionary[5]:",my_dictionary[5])

print("my_list[5]:")

print(my_list[5])

Question: can you retrieve the value for key 5 from the dictionary?

Question: can you retrieve the value for key 5 from the list? Why not?

Now adapt the code by changing the initalization of the list (first line) such that

mylist[5]

contains the value 'F', and as a result print(my_list[5]) actually prints the letter F to screen.

Hint: you need to initialize the list in such a way that 5 is a valid index for the list.

Question: what is the minimum length of the list required to accomplish this?

Question: why is it not possible to define a list (for instance,

my_list) with only 4 items that still produces a value for index 5 (my_list[5])?Question: suppose you have a consecutive list of indices (or integer keys) 0,1,2,3,4,…,100 and corresponding values. Which type of variable is more efficient to store and access these keys and values: a list or a dictionary?

Question: suppose you have a sparse and non-consecutive list of 4 integers (for instance 1,2,10000 and 2000000) and associated values (for instance ‘A’,’B’,’C’ and ‘D’). Which type of variable is more efficient to store and access this particular combination of keys and values together: a list or a dictionary? Explain why!